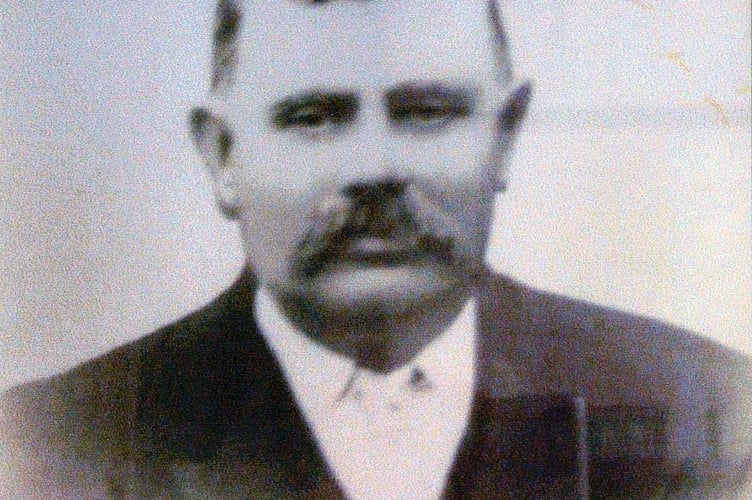

Badshot Lea is probably unique in having a Victorian hop kiln as its village hall. It was built in 1886 for Walter Tice, of Runfold Farm, who the writer, George Sturt, regarded as Farnham’s most successful hop grower.

The Kiln was built with rolling screens on the upper drying floor and the latest hop presses on the floor below. One of the screens and a selection of artefacts are preserved in the Tice room. The builder was Thomas Diamond of Castle Street, Farnham and it cost Walter £1,173.

The drying process was a key stage in hop production, and before pyrometers came in, a skilled dryer was required, as the correct amount of moisture had to be left in the hops. Initially, charcoal fires were used to dry the hops, and small amounts of sulphur were added to kill any insects. I well remember the acrid smell, when walking past the Kiln. Later gas fires were introduced.

Sadly, Walter was only 54 when he died on December 17, 1908, leaving his son Fred Tice to run the farm through the difficult years of the Great War, when many acres of hops were grubbed up to grow food.

There was a sad incident at the Kiln in December 1915, when a private in the RASC, Richard Finlay, hanged himself at the Kiln.

He was suffering from combat stress, after serving with the ambulances in France.

Some growers never planted hops again, but Fred Tice continued at Runfold. Out of season, the Kiln was used in connection with his other enterprise, sending vegetables to Covent Garden Market.

When Fred died in 1940, his brother Alan took over at Runfold, and it was he who began to increase the acreage of his farm. By this time hop poles had been abandoned in favour of coir strings, which were supported by permanent posts and wires.

All this time the Kiln remained in regular use, and until the 1950s the hops were picked by hand by families from Badshot Lea and Aldershot.

The last time I picked hops was in 1954, and the following year Alan Tice installed a hop picking machine, which was housed in the asbestos building next to the Kiln.

The hand pickers were phased out, and students engaged instead, although some local women were still needed to pick out any unwanted leaves. The hops were then placed loosely into bags and sent by an elevator up to the drying floor in the Kiln.

When Alan Tice retired his son Jim took over the farm, which now extended over 398 acres. But by the 1970s, farming at Runfold was coming under new pressures. Common Market regulations clashed with British hop growing methods, the farm was suffering from vandalism, and land was being sought by developers.

Then valuable gravel deposits were found under much of the land. After the gravel had been extracted, the land was allowed to return to nature as Tice’s Meadow Reserve.

Shortly after we moved to Badshot Park, my wife and I were shown over the Kiln in 1972 by the last dryer, Heinz Muller, who was one of several German ex-PoWs, who stayed and married local girls.

The following year the farm was sold at auction and the Kiln, together with the hop picking machine building and 2.290 acres, was sold as Lot 15 to a developer, Mr Cook. It was the end of an era.

By Maurice Hewins